Defense Industry: From Ottoman Period to Today

Until 2000s, Turkey has tied its deterrence capability to conventional weapon systems produced by its allies in NATO while building its defense and security policies. Turkey has adopted “indigenousness”, “being national”, “self-sufficiency”, and “competency” principles.

In the defense industry why does Turkey give such importance to “domestic production”, “nationalization”, “strategic autonomy”, and “competency”? In the defense industry, why is co-production, cooperation/business share and technology transfer essential? How is Ankara planning to get rid of the “one resource dependence” that is brought by purchasing from abroad? In defense policies, how has it struggled for strategic autonomy?

What lies behind these questions are historical codes of defense mentality which date back to the Ottoman Empire.

Consequently, in order to understand the current positioning of the Turkish defense industry on a global scale, the historical development of the defense industry needs to be observed first. In that way, particular breaking points are noticed that symbolize rise and falls of the Turkish defense industry’s historical development.

Each period follows breaking points that contain different characteristic features according to the conjuncture. Those features shed light on the change and transformation of Turkey’s foreign, security and defense policies.

1. OTTOMAN ERA:

The Ottoman Empire existed between 1299 and 1922, and ruled three continents for 600 years or so. Without question, it is impossible to fit the developments in the defense industry throughout whole history of such an Empire into one or two pages.

In this context, we can choose Fatih Sultan Mehmet’s (Mehmet the Conqueror) conquest of Istanbul, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, as a breaking point. With this conquest, the Ottoman Empire started to rise. As a Turkish emperor who defined an era,with the importance given to science and technology, Mehmet the conqueror played a leading part in the development of the Turkish defense industry. For example he drew a sketch of a cannonball called Şahi (Vasiliki), the most effective cannonball of the period with a long range that weighedeight tons and required a minimum barrel length of 91.5 centimeters, by himself and also worked on topics such as ballistics, range, launch, weight and influence together with Ottoman engineers. In addition to the success in cannonball development, Mehmet personally carried out the design and ballistic calculations for a cannon that was used for the first time in the conquest of İstanbul.

“INSTITUTIONALIZATION”, “MASS PRODUCTION”, “DOMESTIC PRODUCTION”

The defense industry during this era depended on steps taken in accordance with “institutionalization”, “mass production” and “domestic production”, not on weapon development, intelligence or human resources. Within this period when crucial developments on cannonball castings took place, with the foundation of the Imperial Arsenal (Tophane-i Amire) a significant step was taken for Ottoman cannonball industry in terms of institutionalization.

THE PERIOD OF STAGNATION AND DECLINE IN DEFENSE

However, from being one of the most powerful states in the world in terms of military and politics in the 16th century, from the early 17th century, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of stagnation and by the 18th century was falling behind. In this context, it is seen that the understanding that gave great importance to the defense industry during the beginning and the period of rise has lost its former functionality during the period of stagnation and regression. The 17th century was a period when the Ottomans begin to lose power in military, technology and the economy. It went to war as defensive a side rather than offensive against European countries and was mostly defeated by the Europeans. As the output of military failures and financial stalemates, the 18th century has gone down in history as a period when Ottomans had to accept the general and technological superiority of Europe; they suffered serious land losses and lost control over the Black Sea and rivers flowing into the Black Sea particularly the Danube.6

Nevertheless, analyzing the regression of the Ottoman Empire from a military perspective, Jonathan Grant objects to the arguments that attribute the reason to the poor quality and inadequacy of military technology of Ottoman Empire as from the 17th century.

Although the Ottoman Empire lost wars and land from 1683, Grant reminds that till 1740, the Ottomans succeeding in to defeating the tsar of Russia, Peter the Great, regaining the lands from Austria and Venice and pushing Iran back. Moreover, falling behind Europe in military technological developments in the 18th century, the Ottomans had managed to catch up with the innovation wave in this field towards the end of 18th century and began to domestically produce and use lots of military products like galleons, frigates, perforation techniques on cannonballs, light field guns, new gunpowder formula and flintlocks.7

In accordance with Grant’s arguments, during the period of Ahmed III (1703-1730) military reforms were made and lots of administrative, financial and social regulations have applied in order to promote these reforms. During the period of Mahmud II (1730-1754) a cannonball foundry, powder mill and rifle factory were established.

Madrasahs were reformed, and a period of learning new information from Europe began. In this context, as the first Western style technical school, the Kara Engineer School (Kara Mühendishanesi) opened. In the Mustafa III era (1754-1774), a rapid gunner artillery was established (sürat topçuları ocağı), and a modern cannonball foundry, shipyard and bulwark engineer schools opened; laws were passed to “institutionalize” the changes made to the navy. On the other hand, focusing on scientific studies, works of mathematics, medicine, astronomy have been brought from Europe and translated. Trying to follow the technical progress of Europe in seafaring and integrating it to the Ottoman system, Mustafa III ordered the opening of a technical school in order to give the first western-style engineering education and to train officers in naval vessel construction and nautical charts.8 Herewith, in 1773 “Tersane Hendesehanesi” today’s Turkish Naval Academy was established by Hasan Pasha of Algiers at Kasimpasa Shipyard. During the period of Abdul Hamid I (1774-1789), these schools were renovated and ship construction has started.9 Janissaries and cavalrymen began to be trained with European-style techniques and arms, artilleries and engineering schools were enlarged. Ships are constructed by taking French and British navies as a model and in this context the Imperial Naval Engineering School called “Mühendishane-i Bahr-i Hümayun” opened in 1784 for naval officers. [Istanbul Technical University and Naval Academy has been established from Imperial Engineering School Naval Academy has moved to Heybeliada in 1851. In 31 August 1985 modern facilities of Academy has been constructed in Istanbul Tuzla. 777 decare land has assigned for Academy.10]

FROM ABODE OF WAR TO DEFENSE

From the second part of 18th century, the Ottoman viewpoint of the West as the “Abode of War” has started to change. Oral Sander indicates that in the 18th century diplomacy takes the place of war as a weapon in terms of the Ottoman Empire’s relations with European states. The Ottomans have understood that from now on its role in Europe is defense, thus it needs allies.11 In same period, negative reflections of the industrial revolution Europe grew, leading to the collapse of some Ottoman industry branches that could not renew themselves through technology.

Under these circumstances Ottoman administrators took various precautions and made an industrialization effort. The first attempts were to enlarge existing facilities and to construct new factories. However these factories were opened in order to meet the military needs.

During these years Selim III (1789-1807) realized that the Ottoman Empire was no longer able to fight enemies by itself and thought that balance policies are inevitable. On the other hand, the complete destruction of the Ottoman Navy by Russians at the Battle of Chios (1770) made Selim III establish “The New Order” (Nizam-ı Cedid) and adopt and implement the latest military and ship construction techniques of Europe.

Within this scope, he tried to improve the engineering schools and initiated the idea of benefiting at the highest level from foreign engineers and academicians as well as holding lectures on ship construction, navigation, cartography and geography. Hereby, in this century the first industrial organizations established by Selim III were in 1793 and 1794 for cannonball, rifle, mine and gunpowder production. Europe’s methods and equipment were to be taken up.12

The difference between Mahmud II (1808-1839) and former sultans was his conception of reform and the way he applied it. Although westernization guided previous reforms, this conception was unable to penetrate into administration and institutions. However, Mahmud II, by taking whole institutions into consideration, put a reform approach built upon a more solid basis.

The most remarkable event of the Mahmud II era is the removal of the janissaries. Since the beginning of the Empire, taking an active role in critical missions, the guild of janissaries had a multiplier effect on the elements that contributed to Ottoman decline. Within the scope of military reforms Mahmud II has disbanded the janissary and Eşkinci corps and established the Mansure Army (Asâkir-i Mansûre-i Muhammediye). During that era, in addition to military reforms, administrative, social, economic and educational innovations were made such as regular population censuses and regulations on asset counting system or opening the military academy “Mekteb-i Ulum-ı Harbiye”, faculty of medicine “Mekteb-i Şahane-i Tıbbiye,” “Mekteb-i Maarifi Adliye” opening technical and engineering schools. Nonetheless, Mahmud II did not put his signature on reforms that directly concerned the defense industry13

By the 18th century, significant industrial developments occurred in Europe. These developments laid the base of the Industrial Revolution which will bring fundamental change over the next century.

Machines that provide efficient and frequent use of coal were invented, and with the invention of the steam engine new developments took plave in the fields like textile, iron industry and railroads. In developing ocean seafaring, great improvements occurred in navigation and sea transportation.

THE YOUNG REPUBLIC DID NOT TAKE OVER SOLID INFRASTRUCTURE

Although industrial revolution in Europe in essence meant a transition from agricultural production to machine technology, for Ottoman Empire this process developed diversely. In the Ottoman Empire before the industrial revolution, manufacturing was dependent mostly on cultivation of agricultural products and munitions production.

Being attentive to the functionality and strength of military and financial power in order to control the dominated geography, the Ottoman Empire had factories built for munitions. Industrial plants such as shipyard, armory, arsenal and powder mill were mostly located in provinces like İstanbul, Salonika, Gallipoli, Bor (Niğde Province) and İzmir.14

For instance, as one of the primary commodities, iron was processed in Samakov, Pravişte and Kiğı; copper processed in Ergani- Maden; lead processed in Keban; saltpetre which is the primary commodity of gunpowder was processed in Konya, Karaman, Niğde, Kayseri and Hezargrad where refineries called “kâlhane” close to mineral fields were sending output to weapon production plants that belonged to the government. Armories were generally located in and around İstanbul however, if required, in order to meet the needs of army armories, powder mills have being built on important routes of the army and navy.15

The defeats of the 18th century demonstrated that the famous Ottoman cannonballs were no longer effective compared to European states and their advanced technology. In the early 18th century there was 60 or 70 percent increase in imports of Ottomans however, towards the end of 18th century the wool and cotton that constitutes half of imports has been replaced with finished goods, mechanic tools, paper, sugar, materials required for seafaring and gunpowder which are required for military industry. Eventually, the Ottoman Empire became externally dependent as they procured commodities needed for military industry and seafaring from Europe.16

Because of the reasons indicated above, for army and the navy, the Ottoman Empire requested military advisers and experts from Britain, France and then Germany with the effort of catching up with the developments in European armies from the 18th century. During the period of Abdul Hamid II, with the participation of military advisers from Germany in reorganization of the Ottoman army, the German weapons industry entered the country.

Major German weapon firms like Krupp, Loewe and Mauser started to meet military needs of the Ottoman army such that in time, Krupp gained a monopoly in the gun ammunition market in Turkey.17

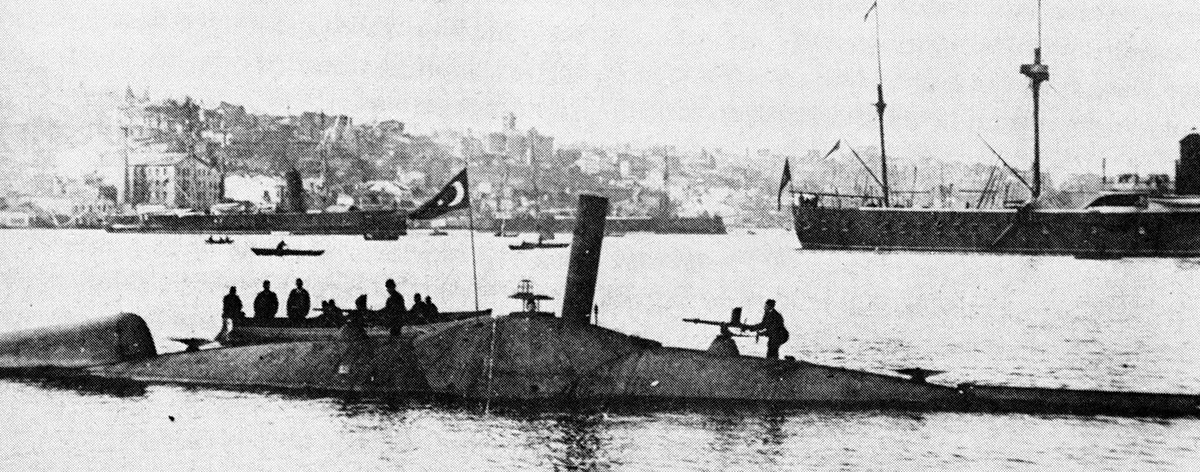

Here, it should be stressed that the Ottoman navy was the second one in history to add a submarine to its stock. Ordered from Nordenfelt Company of Norway in 1886, two submarines were purchased by Sultan Abdul Hamid II paid from the private treasury and joined the navy as “Abdul Hamid” and “Abdul Majid”.18

Only shipyards, armories and maintenance supplies with military supplies that are secretly dispatched to Anatolia during the First World War passed to the new Republic. Activities during the first years of the Republic were limited to a few production plants that were established during the Turkish War of Independence.

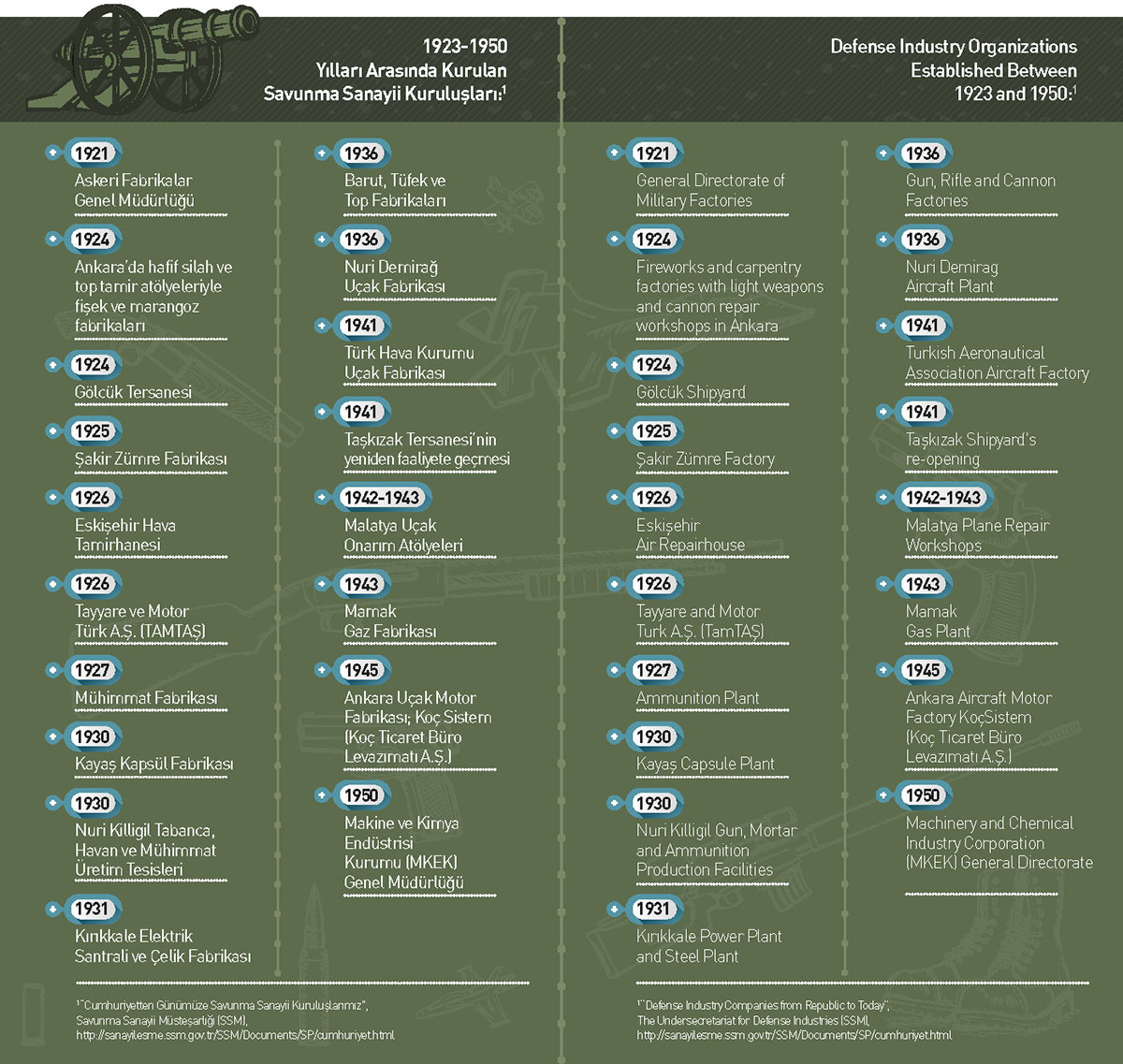

2. EARLY REPUBLICAN PERIOD (1923-1950)

The defense industry in the Republican Period has been accepted as one of the keystones of total industrialization and development and was top of the national priority list. Therefore, the idea of developing and supporting defense industry by the state was adopted. At the Izmir Economic Congress in 17 February 1923, Ataturk mentioned the significance of the defense industry and so the first decision related to the establishment of small arms ammunition plant in Kırıkkale was made during that congress. During this period, government encouraged the establishment of factories in different industrial areas.

Small arms and cannonball repair shops, carpenters’ shop and cartridge factories were established in 1924, The Eskişehir Air Repair Shop and Şakir Zümre Factories were set up in 1925, the Kayseri Aircraft Factory was established in 1926, the Kırıkkale Armory was established in 1927 and a rice factory was established in 1928.

For instance most of the blockbusters of 100, 300, 500 and 1,000 kilograms that are used by bomber aircraft and various firebombs have been produced at Şakir Zümre Factory.

Producing for the Turkish Army often in cooperation with Şakir Zümre Factory, the state owned mechanical chemical industry (İmalat-ı Harbiye) revised its methods and produced for many years. Armories, tampions, practice bombs, aircraft flares and flare guns that the Turkish Land Forces needed came from that factory.

From grenade to tampions and from various land mines to fire bombs almost every armsy that the Turkish Army needed were manufactured by Turkish technicians and masters.19

Also during this period in 1929 the naval shipyards in the Golden Horn (Haliç) were planned to move to Gölcük, and the construction of Gölcük Naval Shipyard has started. In spite of being a newly-established state and negative economic circumstances, shortage of technological infrastructure and expert human resources, it is commendable that investments and factories during the very first years of Republic underpin the national defense industry.

THE BEST AERONAUTICAL FACTORY OF THE ERA: TAMTAŞ

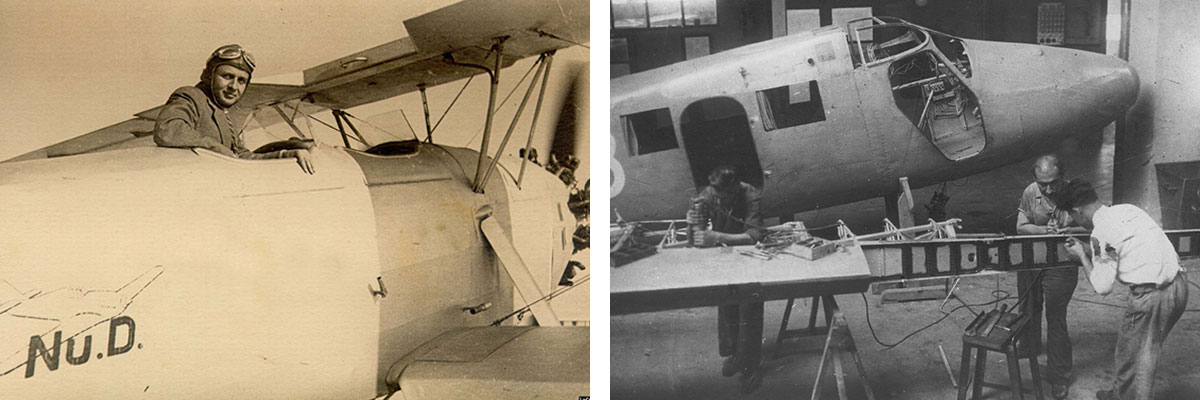

There are two distinct elements that make the Republican Period different. First is enterprise of private firms. The second is significant developments in aviation.

Besides the factories established through government or public aid, during the Atatürk Era private defense industry firms have been established. Within this context, beginning production in 1930 on the Golden Horn in İstanbul, Nuri Killigil Production Plant (Gun, Mortar, and Ammunition Production Plants) is one of the first private firms that serves the defense industry. That company provided Turkish Armed Forces with arms and equipment. Besides, shipyards that remained from the Ottoman Empire have been modernized. In 1929 in order to repair the warship Yavuz, the shipyard on the Golden Horn was moved to Gölcük. Also, a new shipyard has been built in Gölcük and in 1941 Taşkızak Shipyard was reopened. Again, it should be stressed that Kayaş Capsule Plant in 1930, Kırıkkale Power Plant and Steel Plant in 1931 and gunpowder, rifle and cannonball plants were established in 1939.

During this period, significant ground has been covered in the aviation industry as well. In 1926 “Tayyare and Motor Türk A.Ş.” aircraft factory, an incorporated company (TAMTAŞ), was established. Becoming a partner with German firm Junkers, the company’s factories in Kayseri started production in 1928. Here, it should be stressed that both during the Republican Period or the Cold War Era, Germany was the closest ally of Ankara in terms of establishment and expansion of Turkey’s defense industry. Coming to 1939 TAMTAŞ has reached the capacity to produce 112 aircrafts in total. Although the period between 1926 and 1939 was economically tough, the establishment of aircraft factories, gaining ground provided by foreign contacts and becoming a country that has one of the most powerful air forces in the Balkans are developments should be appreciated.

In spite of being the best aircraft factory, because of a “licence conflict” with Germans, TAMTAŞ had to be closed. Following this, aircraft production was interrupted for a while. On the other hand, an aircraft factory was established by the Turkish Aeronautical Association (THK) in 1941 and became a symbol of the first independent attempt and major enterprise in aircraft industry. Among other things it should be stressed that first aeroplane engine factory was established in Ankara in 1948. Besides, aircraft purchased from Britain during the Second World War were repaired in factories in Malatya during that period. Another private company was purchased by Nuri Demirağ. Again, 24 NUD-36 trainer aircraft and NUD-38 airliners with six passenger capacity were manufactured under German licence. However this factory was closed in 1943 or 1944.

AID HALTED FLEDGLING INDUSTRY

After the Second World War, the Turkish aviation sector has had the most expensive investment in the defense industry around the world. The Ankara Wind Tunnel has become the biggest wind tunnel constructed at that time. Starting from 1947, the construction of the tunnel was finished in 1950; research and development and production expenditures of the tunnel corresponded to one-third of the total budget. However phases of project could not be completed, and with the help of the United States research and development, the process was completed in the 1950s.

In 1967 an expert came from France to conduct a NATO field study and indicated that the wind tunnel could be the most successful facility in Europe in terms of its’ design and construction. In 1994 the project attempted a restart but it has remained unsuccessful.

In the early Republican Period, great steps were taken towards the aim of establishment of a national defense industry and new enterprises have been initiated. As can be seen in the list below, the Turkish defense industry expanded in a way to meet the requirements of internal security and become a part of industrialization cycle under the guidance of the state. However it should be stated here that under the scope of the Lend-Lease Act dated 11 March 1941, the United States has provided weapon transfer and ammunition support to various countries such as Britain, China, Soviet Union, France and Turkey.20 As part of the programme, between 1941 and 1944 war equipment worth 95 million dollars was supplied to Turkey by the United States. Besides that, the influences and results of the Truman Doctrine dated 12 July 1947 should be taken into consideration. Up to the 2000s support and aid packages supplied through Truman Doctrine provided the basis for Turkey to ask and use credits from Western economic institutions especially from the United States. Thereby, it paved the way for dependency in terms of politics, military and economy. Although in the early Republican Period, great steps were taken towards the aim of establishment of national defense industry and new enterprises have been initiated, following the Second World War, in addition to the grants and aid that the United States and Britain provided, the increase of military aid with the acceptance of Turkey as NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1952 have caused the development of defense industry, which had just started to crawl, to end.

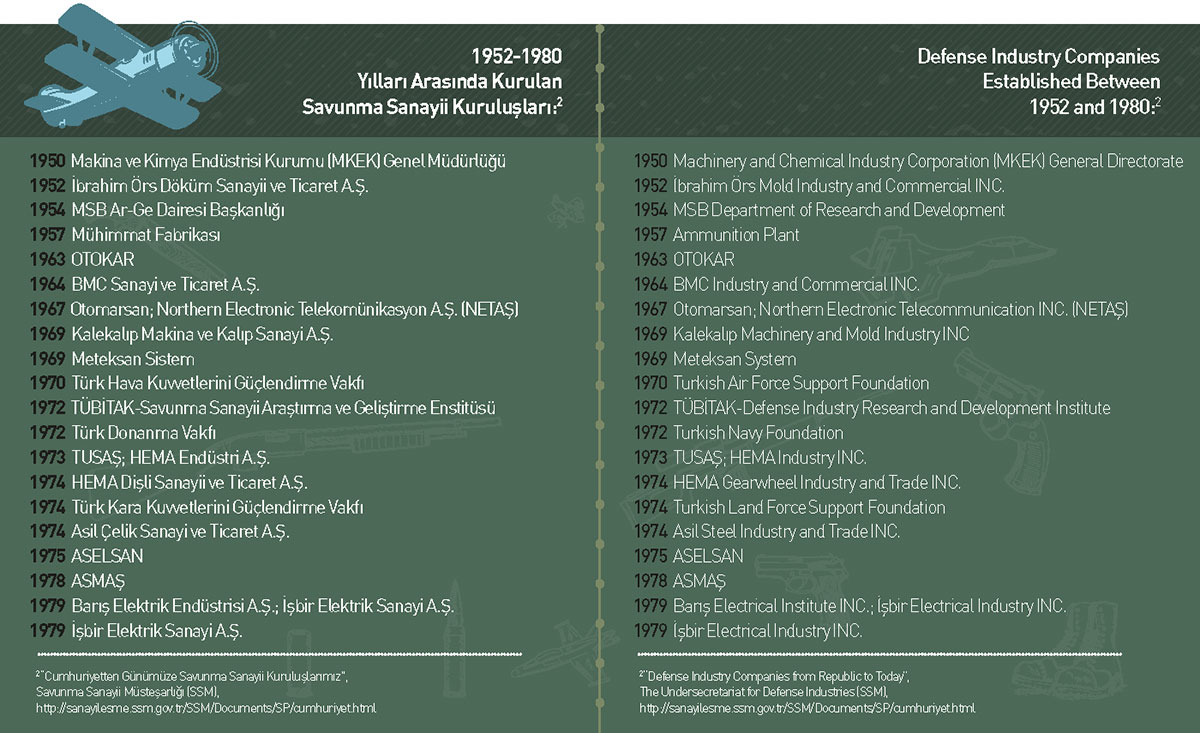

COLD WAR ERA (1950-1980)

In the scope of the new power balance in international politics, how and to which direction did Turkey’s decision to be in the Western bloc and its internal and foreign policy change Turkey’s defense policy?

After the Second World War, while giving importance to participate in regional and international alliances, the main aim for Turkey was to position itself in the umbrella of the Western Bloc. In this manner Turkey became a party to theUnited Nations in 1945, and the Council of Europe in 1949, and became a member of NATO in 1952 and became a part of the Ankara Agreement in 1963. Internal politics posed an obstacle to Turkey and its aims of rapid integration to the West in terms of foreign and defense policies. The Ankara government had to face military coups decennially, the 1960, 1971 and 1980 military coups were breaking points that stalemated Turkey in political, military and economic areas. On the other hand, the Cyprus Peace Operation in 1974 undermined Turkey’s trust and belief in Western allies in NATO. From the Second World War, overrating the value of alliances and bilateral relations in NATO and the European Union (EU) made Turkey restrict its defense approach and policy to American and European markets. Consequently this situation has enhanced sole resource dependency.

It was impossible for Turkey to defend itself against the Soviets due to its economic problems, increased defense expenditures and lack of armament necessary for modern warfare. Developing new strategic planning in order to preserve its private interests and sustain its strength, the United States was aware of Turkey’s situation. This awareness and requirement turned a new page between Ankara and Washington. Undertaking the leadership of the Western Bloc, the United States decided to provide aid to Turkey, which the United States valued for its geopolitics and geostrategic position. The United States also perceived Turkey as a shield in terms of prevention of Soviet expansionism and it introduced this decision with the Truman Doctrine in 1947 and the Marshall Plan in 194821

22 Collaboration between the two countries has moved forward with Turkey’s membership to NATO in 1952 which was founded under US leadership in 1949.

Military and economic aid through bilateral agreements signed between Turkey and the US after Turkey’s membership in NATO caused NATO to be directly tied to the United States. For instance, being unable to recognize which military bases in Turkey belonged to NATO and which to the United States created an impression in public that all foreign military bases belonged to the United States. In a sense NATO and the US were interpreted as equal and NATO became recognized as a reflection of the political discourse and practices of the United States.23

Visiting United States between 30th of May and 4th of June 1954 , Adnan Menderes requested the United States to open long term credits and extend the date of US aid to 1958, and asked the US capital to promote investment and to continue to supply aid in order to modernize and meet the expenditures of the Turkish Army. In response, US president Dwight David Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles promised economic assistance and 200 thousand dollars in military assistance with an increase of military equipment supply to the Turkish Army.24

Menderes’ US visit is the clearest indicator of how Turkey had become dependent on the US in particular and NATO in general in terms of economy, finance and military.

Consequently, granting surplus of goods and equipment to Turkey prevented domestic production and condemned Turkey to the market of NATO. For instance the “Bloody Christmas” events in Cyprus between 1963 and 1964 were the first concrete incident that demonstrated that Turkey had to lower its expectations from United States in terms of meeting defense and security necessities. In this sense, the famous letter of the President of United States Lyndon B. Johnson to İsmet İnönü who was the prime minister during that period caused an earthquake in Ankara.

These lines of Johnson’s are clear reflection of a concealed threat:

“Under Article IV of the agreement with Turkey of July 1947, your government is required to obtain United States consent for the use of military assistance for purposes other than those for which such assistance was furnished. Your government has on several occasions acknowledged to the United States that you fully understand this condition.

I must tell you in all candor that the United States cannot agree to the use of any United States supplied military equipment for a Turkish intervention in Cyprus under present circumstances.” 25 However, Turkey has recognized the meaning of its absolute dependence and the requirement of defense industry infrastructure with the Cyprus Peace Operation in 1974 as an unpleasant experience.

FROM TRACTOR FACTORY TO ALTAY

As industrialization gained momentum in the 1970s, Necmettin Erbakan gave great importance to “indigenousness”, laying the foundation of various factories and promoting the idea of “let’s make our own tank”.

Although this approach mattered greatly for the defense industry, at that time, there was no infrastructure, knowledge base, or research and development capacity or financial resource. It should be recognized that TÜMOSAN, Turkey’s premier tractor and diesel engine producer established by Erbakan when he was deputy prime and government minister in 1975, is now developing a diesel engine for the Altay tank today.26 In the light of foregoing, we can collect striking features of the Turkish defense Industry from the 1950s to 1980s under five headings:27 First is the transformation of arsenals that had a key role in the development of Turkish Defense Industry to state-owned economic enterprises. In this sense, the Directorate General of Arsenal (Askeri Fabrikalar Umum Müdürlüğü) was transformed to a state-owned enterprise called the Machinery and Chemical Industry Cooperation (MKEK) in the early 1950s and directed by the Ministry of Operations as the enactment of MKEK Law no. 5591. Also the Law no. 5591 authorized MKEK to purchase from the Turkish Aeronautical Association.28 The second is credits and assistance from abroad due to recession in the Turkish Defense Industry. Within this context, aid from the United States under the Truman Doctrine came in four areas which are grants, Foreign Military Funds (FMF) and Foreign Military Sales (FMS) credits, commercial credits and training support. For instance thanks to this aid, Turkey was able to obtain M-47/48 tanks, artillery, aircraft and equipment. However, during the 1970s grants decreased gradually. Still, during that period, through grants, Turkey gained F-4E (Phantom II),29 T-38 aircrafts and Perry class frigates in its stock. On the other hand, following 1972, Turkey has received foreign aid through credits as part of FMF and FMS. However as embargoes took place between 5 February 1975 and 26 September 1978 justified by the Cyprus Peace Operation, the United States stopped those aid between 1975 and 1980. Thereby, credits provided through foreign aid were cut for five years. In March 1980 “the Defense and Economic Cooperation Agreement” 30 between the USand Turkey was signed, and the FMF and FMS programme restarted in 1980 and lasted till 1998. At first those credits were given as grants but then transformed into long term loans at 5 percent interest. It should be indicated that Turkey had tuition assistance through a programme called “International Military Education and Training”. The cost of activities within this programme equals to one or two million dollar per annum. Here, it should be noted that Turkey received foreign aid not only from the US but also from Germany. Foreign aid and grants impeded Turkey’s efforts to establish a national defense industry and caused recession in Turkish Armed Forces domestic orders. This situation led arsenals to weigh on national budget as they lost efficiency. Arsenals were transferred to MKEK. For instance, while Turkish Aeronautical Association had been producing THK-5A transport airplanes and was exporting its ambulance version to Denmark, when the aircraft factory was transferred to MKEK it was transformed into a textile factory in 1968.

Third is Turkey’s domestic efforts. During this period, it is possible to talk about Turkey’s steps to move the Turkish defense industry forward. Within this context, establishment of Ammunition Plant conforming to NATO standards in 1957, formation of rocket factory and gear manufacturing facilities, production of Cobra Anti-tank Rocket, G3 service rifle and MG3 machine gun by MKEK in 1967 can be considered as examples. However these efforts remained restricted. Political and military decision making mechanism was unable to recognize the extent of the negative influence of grants and aid on the national defense industry. In other words, the gap in terms of sustainability due to the lack of transfer of technology and armament could not be recognized. However, foreseeing the potential impact of US aid on their national defense industry, European countries took precautions to avoid dependency. Then, again, Turkey noticed this situation first during the Cyprus events in 1964.

Fourth is the 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation. Even though Cyprus events in 1963-64 created an awakening in Ankara, the experience of 1974 was more brutal and harsh. In spite of being a NATO member, Turkey faced an arms embargo from US, a part of the same alliance. Thus, Turkey had to supply required bullets and auxiliary equipment from Libya. Although the arms embargo played a critical role in terms of developing Turkey’s defense industry, its reflections and consequences during that period were harsh. Here it should be noted that although there was no embargo in the 1990s and 2000s, Turkey has suffered from tacit embargoes on many occasions. For instance, during the 1990s when PKK terror was at its peak in terms of counter terrorism efforts, Turkey has wanted to purchase AH-1W Super Cobra Helicopter for defense purposes from the United States. However, because of the pressure of public opinion caused by various interest groups, especially Greek and Armenian lobbies, the Clinton Administration did not approve this purchase because of the dynamics of internal politics and did not activate the FMS channel and did not provide feedback to Congress. In addition to the tacit embargo, technical reasons that prevented the Clinton Administration from consulting Congress about the purchase should not be disregarded because it is almost impossible to make the sale if Congress has not approved it. Accordingly if rejection is a possibility, it is logical not to present the deal to Congress. Similarly, in the 2000s the US Congress did not allow the sales of Reaper drones and Cobra helicopters which Turkey intended to purchase from the United States.

Even so, three years ago in January 2015, Congress refused the sale of three FGG class guided missile frigates which were surplus for the American Navy and refused the reduced price sale of a warship.

Congress has approved the sale and grant of frigates to Mexico and Taiwan which are not members of NATO.31 Finally, Turkey has adopted the self-sufficiency understanding in weapon production by itself. For instance, under the scope of Law no. 3238 the “make your own aircraft” slogan has become very popular. As an outcome of this policy, various attempts have been made for sectoral development on the basis of power.

Within this framework, Turkish Air Force Support Foundation, Turkish Navy Foundation, TUSAŞ, Turkish Land Forces Support Foundation and ASELSAN has been established. Turkish people made donations to these foundations and special income sources has been granted to these foundations/ companies by law.

Meanwhile, it has been observed that political and military decision makers have increased their awareness about the importance of R&D activities as a result of events experienced during those years. (At the same time, there were strong criticism about these companies and MKEK mainly saying they were using old technologies and overemployed and these facts prevent them to compete in the international market).

1980s- NEW OPENINGS

Coming into power with 1983 elections, Turgut Özal left behind a significant heritage of economic reforms, proactivity and entrepreneurship in the defense industry.

Generally, during the Özal era (1983-1989) vital importance was given to financial liberalization, economic growth based on exports, the promotion of a dynamic and entrepreneurial sector in Anatolia, initiation of enterprises in the fields of politics, culture and foreign policy and to the expansion of its’ influence zone.32

For instance, the application to the European Union for full membership in 1987 was actually an outcome of his pragmatic approach which has a geopolitical and economic basis.

Although embracing an expansionist approach in foreign policy, Özal was sensitive to the criteria of being domestic and national. There is no doubt that, as an engineer, Özal brought a technocratic approach to politics and reinforced attention on research-development and production. From the beginning of the 1980s companies like Turkish Aerospace Industries (TAI), ASPİLSAN Energy Industry and Trade Inc. were established and investment in the defense industry increased. Also with the Defense Industry Development and Support Administration Office (SaGeB) the establishment of the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation (TSKGV) was one of the most significant developments during this period. It will be clearer to explain the defense industry under Özal with three headlines. The first is liberalization efforts in the Turkish economy.

Before the 1980s the political economy was based on import substitution. In this model, which was based on cooperation with exporting countries, weapons previously imported from abroad could be produced in country on the condition of buying a licence. However the small size of the market, and structural and financial problems made modern weapon production impossible because heavy investment was needed.

Although facing with similar problems to Turkey, countries like Brazil, India and Israel succeeded to produce modern weapons as they gave great significance to the defense industry. On the other hand, applying import substitution model from the beginning of 1950s, Turkey did not contribute to the defense industry. Because of economic inconsistency, Özal adopted a different model . The new model was to restrict the state’s role in economic and trade activities to structural and socioeconomic investments. Although the state monopoly has sustained its presence in the defense industry till 1985, private companies that were banned from entering the defense market started to be encouraged after 1985. Secondly, in 1985 law no. 3238 was introduced. Aiming to produce all weapons and equipment that were economically possible in Turkey, Law no. 3238 brought a new defense industry approach and an elastic system that moves fast. In order to develop the defense industry and modernize Turkish Armed Forces, Defense Industry Development and Support Administration Office (SaGeB) was established. Moving from the necessity of continuity, resource requirement and state intervention, SaGeB has been reconstituted as The Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (SSM) in 1989 for central implementation and coordination of work in the defense industry. Moreover, the Five-year Development Plan (1985-1989) anticipated investments to develop the defense industry. Lastly, with project-based industrial enterprises, the Turkish defense Industry leaped forward. In that context, industrial enterprises listed below have conducted significant projects. It should be criticized that, despite Özal’s sensitivity towards research and development studies, this field has always been disregarded. The budget for research and development was only 0.3 percent of the Ministry of Defense’s budget.

OFFSET LOGIC

Although Özal’s approach is described as an import substitution model, it offered an insight into today’s world with its national and domestic production enterprises.

Özal’s main motivation that changed the settled mindset was an offset logic that has been brought into the defense industry. Turkey gained the ability to export through offset logic. Within this context, one of the main legacies of Özal is Turkish Aerospace Industries Inc. (TAI). In the simplest term, F-16 production of TAI is an incredible success story. It should be kept in mind that today, Turkey uses the F-16 for cross-border operations like Olive Branch Operation or Euphrates Shield. TAI has a dominant role in Turkey’s exports in terms of the defense industry.

According to the Defense And Aerospace Industry Exporters’ Association (SSI), export figures for defense industry in 2017 increased 3.7 percent and reached 1 billion 739 million dollars from 1 billion 677 million dollars in 2016. TAI has become a champion in the defense and aerospace industry.33

Nurol Defense Industry Inc., which has benefited from resources presented by Özal has partnered with FMC and BAE Systems to become the leading defense industry exporter.34

1990s – RECESSION

Defined by coalition governments and crises, the 1990s saw no ground gained in terms of the defense industry. Still, efforts to modernize the Turkish Armed Forces and importance given to technology should be stressed.

In accordance with aims and policies revealed by Law no.3238, the procurement approach between 1990 and 2000 changed from direct procurement to co-production. However, the cabinet decision on Turkish Defense Industry Policies and Strategic Regulations is a milestone for the Turkish defense industry.

Within this decision, primary elements for defense industry listed below has been identified:

- Domestic and foreign private sector

- Dynamic Structure

- Export potential and possibility of international cooperation

- Ability to adapt to new technologies

- Balanced defense industry cooperation between Turkey and allied countries

- Minimum response to changing political circumstances

- Maximum benefit from existing opportunities, purification of integrated and re-investments.

- Production with civil purposes, alternative field of focus.

- Promotion of duties and priorities toward export regimes to which Turkey is a party.

Lastly, attention should be drawn to two developments during the 1990s. The first is the foundation of “Defense Technology, Engineering and Trade INC.” (STM). The second is publication of “The White Book- Beyaz Kitap“ which formulates national defense policies in 1998.

It adopted new strategies based on elements like deterrence, military contribution to crisis management, forward defense and collective security.

2000s – ON THE ROAD TO THE NEW TURKEY

This period started after the AKP under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came to power in 2002.

During this period a new orientation process started from a Turkey that theoretically transferred its security and defense policies to NATO and met its needs from the United States and NATO through foreign procurement, to a new Turkey that can make independent decisions in line with self- determined strategies, and investments dependent on its own capital.35

There are three major concepts at the center of the new defense and security perception: “domestic production”, “nationalism” and “strategic autonomy “.

Since NATO membership in 1952, Turkey has shaped its national defense policy through the Atlantic Alliance. Consequently, as part of restrictions caused by the Cold War, Turkey’s supply chain consists of NATO allies satisfying the needs of the country.

However, the cooperation with the US in particular and NATO in general on security and defense, has been cut multiple times. During the Cold War period, due to disagreements especially with the US, Turkey started to seek a relative “autonomy” in terms of its defense policies. However, western and US based features of the security bureaucracy of Turkey prevented it from following the desired strategy, and the establishment of a domestic defense industry was delayed. This situation condemned Turkey to dependency in terms of the defense industry.

Turkey was facing obstacles while struggling with security threats. Crises in the scope of 1974 Cyprus Peace Operation and political disagreements over the matter of counter terrorism are the first examples that came to mind.

Although some attempts to establish civilian control had been made during the Özal Era, because of the lack of democratic control of civil-military relations and the exceptional role of the military in politics, Turkey was unable to eliminate the dependency issue in terms of defense.

During the 1990s, the Turkish Armed Forces was behaving free and separately from government in terms of shaping and determining political agenda especially on security and defense policies. This was a problem.

The Turkish Armed Forces carried out a tank modernization agreement with Israel without Refah-Yol Government authorization. This exemplifies the situation between the TSK and the government.

On the other hand, the security environment was transformed after the Gulf War and Iraq invasions and then the failed Arab uprisings.

The counter-terrorism efforts that evolved into warfare demonstrated how vitally important the indigenousness principle is. Here, the principle of being national has been considered not only in terms of meeting the needs of the defense industry during war or in the conventional operational field, but also in terms of all fields that concern national security. Briefly, the principle of being national means minimizing external dependency through self-ability to meet defense necessities with domestic resources.

Nowadays, considering the sophistication of weapon systems and air and missile defense technologies, it is obvious that long terms investments are essential. Thus, having this ability is not only about the economic level of the country but also about human capital, infrastructure, scientific studies, research and development capacity, and technology level.

In spite of enormous oil revenues, the resource and technological dependency of Middle East countries illustrates the situation. Likewise, the need for a national air and missile defense system, essential after the Arab uprisings, is another example. The long-range, high-altitude regional air and missile defense systems that Turkey needs are under the monopoly of various countries.

Purchasing these systems is a primary element of global defense rivalry. In addition. problems associated with defense alliances and sui generis issues with in its own security complex have complicated Ankara’s supply process.

As is known, Turkey prefered China’s FD-2000 (HQ-9) defense systems because of its technical and financial advantages. However, because of the security problems between US, NATO and European allies and conflict of national interests, Turkey turned towards the S-400 defense systems T-LORAMIDS tender offer of Russia.

While deciding, Turkey has taken foreign supply criteria, technology transfer, common production requirement, domestic contribution, delivery time and price advantage into consideration.

During that process, Turkey has also put a low and medium altitude defense system project into action, demonstrating persistence in terms of minimizing its resource technological dependency.

“INDIGENOUSNESS”, “BEING NATIONAL”,

“STRATEGIC AUTONOMY”

There are three major concepts at the center of the new defense and security perception. These are: “domestic production”, “nationalism” and “strategic autonomy“.

Turkey’s policy on the establishment of national defense systems does not only consist of indigenousness. What is complementary to this principle is the idea of “being national”. Thanks to the systems and successful designs that integrate sub-systems supplied from domestic and foreign producers, the national product range is increasing and becoming varied. The crucial point here is the improvement of integrated models that gather technologies critical for competition in international markets. While gaining ability and competency, it is important not to depend on limited foreign resources in obtaining critical technologies.

Turkey’s defense policy is designed in accordance with the long-term macro strategic purposes of the country. Today, on a regional scale, ever expanding uncertainties reinforce the risks to national security. As the arguments over S-400 indicate, purchasing a “platform” alone is inadequate to meet the long-term needs of Turkey and carries a high risk of dependency. Thus, Turkey should not disregard production of national missile defense systems even while supplying it from foreign platforms. It is important to put these systems into service as soon as possible.

Although the Russian defense system meets the requirements on a technical level, as an inseparable piece of Turkey’s NATO security umbrella and the Alliance’s Missile Shield Project, the political and strategic complications indicate how important “self-determination” is.

Strategic autonomy is a supplementary element of “being national” and “being domestic”. Autonomy can be described as the ability to establish an independent sector in the defense industry on a tactical and strategic level and its adaptation to national security strategy and doctrine and the current needs of the Turkish Armed Forces, to eliminate national security threats. For instance, by decreasing its dependency via independent air and missile defense systems that are improved by domestic and national resources, in the long term, Turkey will increase its’ military deterrence through self-determination.

Turkey is surrounded by countries with different political and cultural backgrounds. Turkey is surrounded by countries that are accused by the international community of being a threat to international security. Most often mentioned are Iran, thought of as a country with the capability to develop nuclear arms, Syria, which has no hesitation to use chemical weapons, and Iraq which is used as PKK base.

During the 2000s, the Erdoğan Era, the defense industry has gained momentum. Getting through the 2001 economic crisis and the continuation of political consistency has played a great role in this momentum.

However, Erdoğan’s confidence and strong will should not be disregarded. Within this scope, the Defense Industry Executive Committee (SSİK) meeting represents the first break-point. Tenders of modern tanks, drones, attack helicopters and tactical reconnaissance helicopters valuing 27 quadrillion lira were cancelled.36 The main justification for this decision was the astronomic prices of these tenders.

Establishing a project that preserves domestic production and original design and benefits from domestic capability is considered essential.

Within this context, Erdoğan has given priority not only to the domestic production of goods which are a design of foreigners but also to domestic projects in which the intellectual property rights are fully-owned. However, for the production with domestic resources the last word does not belong to you. For instance, while the CİRİT (laser guided missile) can be used in Atak Helicopter which is a domestic product, it cannot be used in the Utility Helicopter which is jointly produced with Sikorsky Thanks to Erdoğan’s willpower and tenacity during the 2000s a great distance was covered in the establishment and development of domestic and national products like ATAK helicopter, the Utility Helicopter, Hürkuş, Altay Tank, and MİLGEM.

60 % OF THE REQUIREMENTS

SUPPLIED FROM HOME

In conclusion, up to the 2000s, Turkey has attributed its defense and security policies to deterrence that is provided by conventional weapon systems supplied by NATO allies. However, during that decade Turkey adopted the “being national”, “indigenousness” and “self-determination/ autonomy” principles. For this purpose, Turkey aims at the establishment of a strong national defense industry which has the ability to produce advanced weapons and which is domestic, national and sustainable. Without a doubt, the success of the new defense understanding that prioritizes technology through domestic and national resources and rescuing Turkish defense industry from external dependency depend on know-how capacity, qualified manpower as well as economic and financial power. These depend on political stability. The defense industry benefited from political stability that came with single-party government after the 2002 elections and from the advantages of economic growth that follow the escape from the 2001 economic crisis. It can still meet the requirements of the TSK domestically.

The coverage ratio in terms of fullfilling the needs of Turkish Armed Forces in 2002 was 25%. In 2007 it was close to 50 % and in 2011 it was more than 50%. Today this ratio is about 60%. The remaining 40% includes the ongoing research and development of sophisticated technology products. On the other hand, during this period, the total cost of the expenditures on modernization projects that TSK needed was 24 billion dollars of which 90% of the projects were applied through participation of local industry. Hereby, there is a 10% decrease on imports of final defense goods. While research and development expenditures were above 50 million dollars in 2002 in 2010 it reached 500 million dollars. Moreover, the turnover of the defense industry, at one billion in 2002, has reached 2.3 billion dollars in 2011.

In this context, it must be stated that a high sensitivity towards the distribution of the sufficient work share was shown by the AK Party administration — especially through the new industrial participation and offset regime initiated in 2011 and so the Undersecretariat for Defence Industries (SSM)’s obligation for IP/O liability percentage, not being lower than 70% of the Procurement Contract value , which has become the case for entire tenders.37

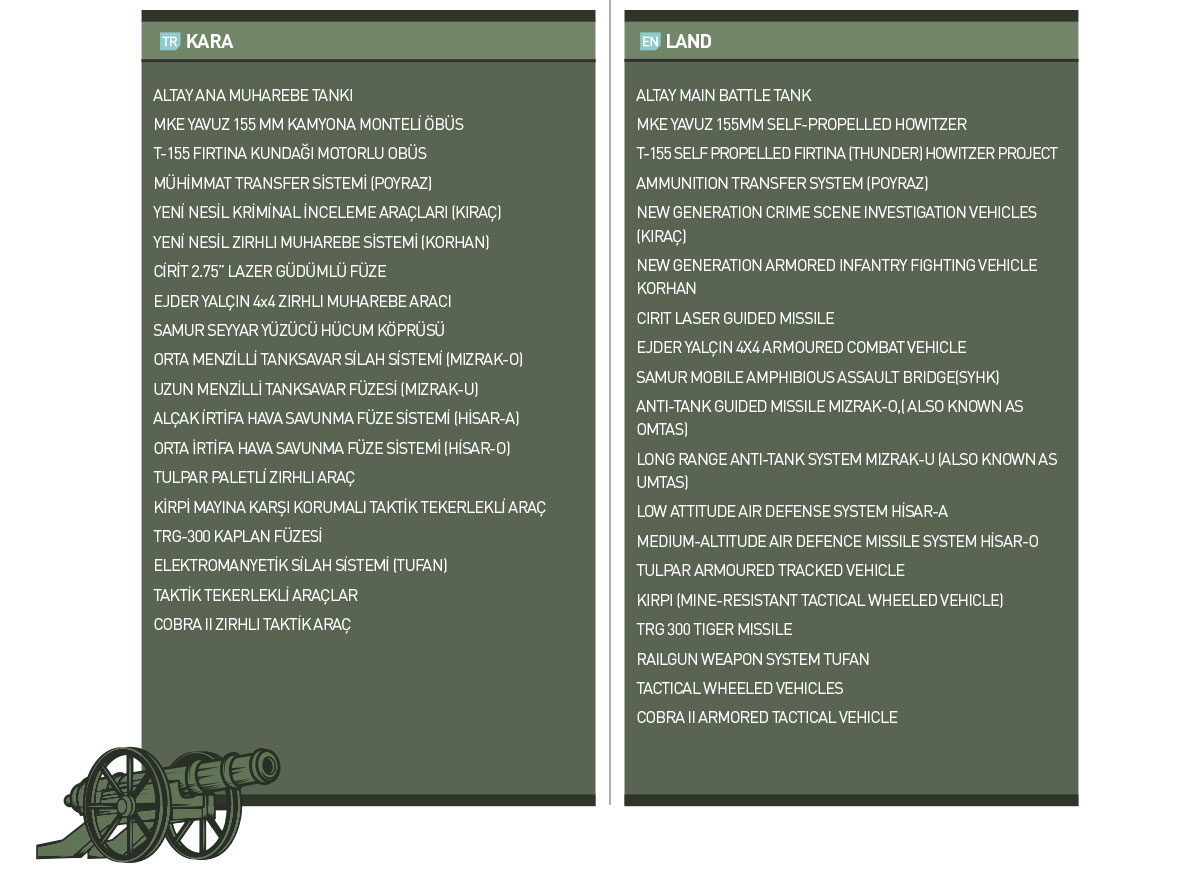

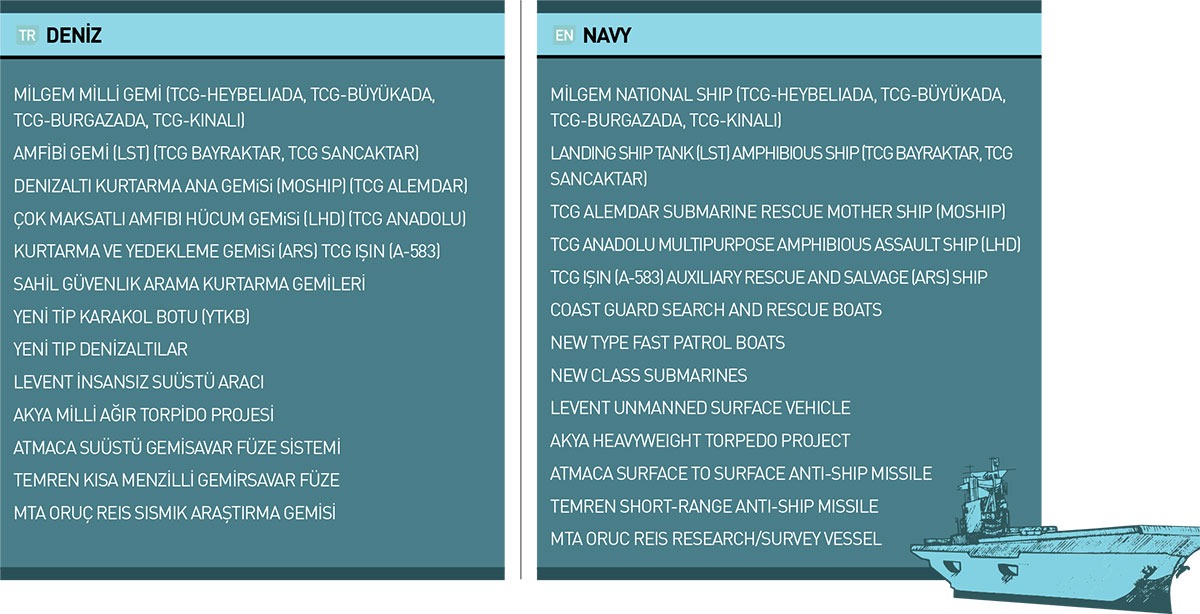

EXAMPLES FROM THE MAIN DEFENSE

PROJECTS OF 2000s

The following defense projects are classified by domains of warfare (land, sea, air, space and cyber) and weapon & missile systems. These are the most prominent projects (across 600 ongoing projects) that have entered the inventory in the 2000s or have a project start date during that period.

Annotations

1Activities of Imperial Arsenal in Ottoman Empire, An example for he studies of ball casting and gunpowder see. Ágoston, Gábor “Western Gunpowder Technology and Ottomans in 15th century”, Social History, June, 1995, pp. 10-15; Aydüz, Salim Imperial Arsenal and Ball Casting Technology, Turkish Historical Society Publications, 2006, Ankara; Tunc, Safak Imperial Arsenal and Casting Activities in Ottoman, Kişisel Yayınlar Publishing Company, İstanbul, 2004.

2The number of cannonballs produced in Imperial Arsenal, was 673 in 16th century, 785 during July 1684 -June 1685, 324 during October 1685 July- 1686, 298 during December 1691- April 1692, 177 during August 1706- December 1707, and 47 during July 1756- July 1757. In contrast to cannonball production, the productions in gunpowder factories which are the base for Arsenal, has increased unevenly. For example, in1571 the output of gunpowder factories in Istanbul was 97.000- 197.000 kg. After two centuries in 1793-94 it has decreased to 84.000 kg see. Koktas, Altug Murat and Golcek Ali Gokhan, “Industrial Revolution and Ottoman Empire: an example of Being Military Factory”, Omer Halisdemir University Journal of Faculty of Economics and Social Science, October 2016; 9(4), s. 101; Yilmaz, Fevzi “Cannonballs during Fatih Sultan Mehmet Era and Changing Production Paradigm”, Journal of FSM , Vol 4, 2014 Guz, pp. 219-236; “Our Defense History: 1923 and Before 1923”, Undersecretariat for defense Industries (SSM), https://www.ssm.gov.tr/WebSite/contentlist.aspx?PageID=47&LangID=1

3Inalcık, Halil and Arı, Bulent “Ottoman Empire as a naval force”, International Piri Reis Symposium, İstanbul, 27-29 September 2004, The Book of Rescript, pp. 2/20-2/30.

4The Battle of Lepanto, Ottoman Sovereignty on Seas, for an historical study that encompasses topics like The Formation of Ottoman Navy see. Bulent Arı (ed.), Turkish Naval History, T.C. Prime Ministry the Undersecretariat for Maritime Affairs, Ankara, 2002. Arslan, Sadik Turkish Defense Industry in the scope of Turkish Economy, Eskisehir, 1990, p. 84 Koseoglu, Ahmet Murat Reconstruction in National Defense Industry Social Policies, Izmir Dokuz Eylul University, Unpublished PhD Thesis, 2010, p. 55

5Simsek, Muammer Defense Industry in Third World Countries and Turkey, SAGEB Publications, Ankara, 1989, Koseoglu, Ahmet quotes from p.23 Murat Reconstruction in National Defense Industry Social Policies, İzmir Dokuz Eylul University, Unpublished PhD Thesis 2010, p. 55

6For a study on submunitions in Ottoman Empire’s stock in 18th century see. Demlikoglu, Ugur “Submunitions in Ottoman Empire’s Orient Castles in 18th Century “, Firat University Journal of Social Sciences, Vol: 24, Issue: 2, 2014, pp. 277-294

7Jonathan Grant, “Rethinking the “Recession” of Ottoman Empire: Expansion of Military Technology in Ottoman Empire (From 15th to 18th century )” (translator: Salim Aydüz), Yakın Dönem Türkiye Araştırmaları, vol:19-20, October 2010, pp. 73-75; Still, for a study that cites military transformation; technologic developments, war tactics and strategies of Ottoman Empire and Ottoman Empire’s dominance over Iran through these developments see. Ozturk, Temel, “Implementation of Military Transformation of Ottoman Empire on Orient blockades in the first half of 18th”, Journal of History, issue: 45, 2007, pp. 57-75.

8Karagoz, Mehmet, “Reforms in Ottoman Empire and efforts on becoming a Western Civilization (1700-1839)”, Ankara University, Journal of OTAM, Vol: 6, 1995, pp. 177, 182-186, 193-194..

9Mühendishane-i Bahr-i Hümayun is indicated as the core of todays’ Istanbul Technical University and Naval Academy which are the two significant educational institutions for detailed information for Imperial Naval Engineering School see. Kacar, Mustafa “From ship engineering school to Marine School “Imperial Navy Engineering School”, Journal of Ottoman Science Studies vol:9, issue: 1/2, 2008, pp. 51-77

10See National Defense University Naval Academy (Introductory Booklet, http://msu.edu.tr/tanitim/DHD/DHO_10 _Ocak.pdf

11Turan, Namik Sinan “The change of Western Image in Ottoman Diplomacy and the Influence of Ambassadors (18th and 19th Centuries)”, Trakya University Journal of Social Sciences Vol: 5, issue: 2, December, 2004, p. 59; Oral Sander, The rise and fall of Phoenix: A study on History of Ottoman Diplomacy, Ankara University Faculty of Political Science Publications, Ankara, 1987, p. 96.

12Kacar, Mustafa “From ship engineering school to Marine School “Imperial Navy Engineering School”, Journal of Ottoman Science Studies, Vol: 9, Issue: 1/2, 2008, pp. 52,59; Seyitdanlıoglu, Mehmet “Ottoman Industry in Tanzimat Reform Era (1839-1876)”, Journal of Ottoman Science Studies , Vol: 28 issue:46, 2009, p.58

13Karagöz, Mehmet “Reforms in Ottoman Empire and efforts on becoming a Western Civilization (1700-1839)”, Ankara University, Journal of Ottoman History Research and Application Center (OTAM) Vol: 6, 1995, pp. 193-194

14Gábor Ágoston, “Behind the Turkish War Machine: Gunpowder Technology and War Industry in the Ottoman Empire, 1450–1700” in B. D. Steele and T. Dorland (eds), The Heirs of Archimedes: Science and the Art of War through the Age of Enlightenment (Boston, Massachusetts, 2005), p. 115; Gábor Ágoston, Powder, Cannonball and Rifle Military Power and Weapon Industry of Ottoman Empire translator: Tanju Akad, Kitap Publishing Company, İstanbul, 2006

15Also see. Soyluer, Serdal “An example of investment of Ottoman Heavy Industry: Yalı Köşkü Iron and Machinery Plant”, Journal of Ottoman Science Studies, 18/2 (2017), pp. 1-23

16Elibol, Numan “Appreciations on Ottoman Foreign Trade during 18th Century”, Eskisehir Osmangazi University, Journal of Social Sciences, Vol: 6 Issue: 1, June, 2005, p. 64

17Besirli, Mehmet “German Arms in Ottoman Army during Abdulhamid II. Era”, Gaziosmanpaşa University Journal of Social Science Institute Vol: 16 2004/1, pp. 121-139

18Mercan, Evren “First Submarines of Ottoman Navy: Abdulhamid and Abdulmecid”, Journal of Security Strategies (8:15), June 2012, pp.163-184

19Oral, Atilla “Private sector enterprises in Turkish Defense Industry”, Defense and Aerospace Journal, Issue: 116, pp. 109-112

20“Historical Highlights: The Lend-Lease Act of 1941” (March 11, 1941), History, Art & Archives United States House of Representatives, http://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1901-1950/The-Lend-Lease-Act-of-1941/

21Turkish government has directly applied to US government for its’ inclusion to Marshall Plan. In this application it stressed the significance between economic situation and military and political consistency. US, has recognized this request and demanded some changes – like giving priority to the extraction of chromium from the ground which is vital for American Defense – for Turkey to be benefited from Marshall Plan. US has decided to supply financial aid and Economic Cooperation Agreement signed in 4 July 1948. However, public view, different political sections and intellectuals did not welcome the agreement and has interpreted as an agreement that consists dependency to US because of the removal of capitulations during Ottoman Era. Çagrı, Erhan “Turkey’s relations with US and NATO ”, Baskın Oran (ed.), Turkish Foreign Policy, Facts, Documents and Remarks from Turkish War of Independence till nowadays Vol I, Issue 6, İstanbul, İletişim Publications, 2002, pp.540-541

22Bagcı, Huseyin Turkish Foreign Policy in 1950s, Issue:3, METU Publishing, Ankara, 2007, pp. 5-7, 37-38

23Erhan, Çağrı “ABD and NATO Relations”, Baskın Oran (ed.), Turkish Foreign Policy, Facts, Documents and Remarks from Turkish War of Independence till nowadays, Vol I, Issue 6., İstanbul, İletişim Publications, 2002, p. 543; Senyuva, Ozgehan and Ustun, Cigdem NATO-Turkey Relations: Turkey’s Public view and Perceptions of Elites(ed. Mustafa Aydın), Istanbul Bilgi University Publications, İstanbul, 2013, pp. 16-17

24Irmak, Ozge Overseas Trip of Adnan Menderes, İstanbul University Institute of Ataturk’s Principles and History of Turkish Revolution, Department of Ataturk’s Principles and History of Turkish Revolution, Unpublished PhD Thesis, 2009, pp. 90-91

25For full text see. “Johnson Letter”, http://www.akintarih.com/turktarihi/cumhuriyetdonemi/johnson_mektubu/johnson_mektubu.html

26“An Engine From Tümosan established by Erbakan to Altay”, Milliyet, 14 August 2014, http://www.milliyet.com.tr/erbakan-in-temelini-attigi/ekonomi/detay/1925385/default.htm “Factories of Erbakan Hoca”, Milli Newspaper , 11 November 2016, https://www.yeniakit.com.tr/haber/turkiyeden-bir-erbakan-gecti-iste-erbakan-hocanin-fabrikalari-233589.html

27Efsun Kızmaz, Turkish Defense Industry and Undersecretariat for Defense Industries, Master’s. Thesis, Department of International Relations, Bilkent University, Ankara, September 2007, ss. 58-62

28For detail information for MKE see. Yurtoglu, Nadir “An enterprise in Turkish Defense Industry: Machinery and Chemical Industrial Corporation (MKEK) 1950-1960”, Recent Period Turkish Studies, 2017/1, Vol: 16, issue: 31, pp. 81-112

29It should be noted Not all F-4E has been purchased as second hand; first 80 aircrafts are has been purchased by national budget between 1973 and 1980s and are first hand

30See. “The Defense and Economic Cooperation Agreement-U.S. Interests and Turkish Needs”, Report by the Comptroller General of the United States, May 7, 1982 https://www.gao.gov/assets/140/137457.pdf

31Seren, Merve “Turkey’s Missile Defense System: Tender Process, Main Dynamics and Actors”, SETA Publications, August 2015, p. 53

32See. Öniş, Ziya “Turgut Özal and his Economic Legacy: Turkish Neo-Liberalism in Critical Perspective”, Middle Eastern Studies, Volume. 40, No. 4 (July 2004), pp. 113-134

33“TAI flies to export championship”, Anadolu Agency, 26 January 2018, https://aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/tai-ihracat-sampiyonluguna-uctu/1042910

34See FNSS, http://www.fnss.com.tr/kurumsal/hakkimizda/tarihcemiz

35As an example of studies which has a different perspective on developments of Turkey’s defense Industry in 2000s see. Bagcı, Huseyin Kurc, Çaglar “Turkey’s strategic choice: buy or make weapons?” Defense Studies, (17:1) December 2016, pp. 38-62; Mevlutoglu, Arda “Commentary on Assessing the Turkish Defense Industry: Structural Issues and Major Challenges”, Defense Studies (17:3), July 2017, pp. 282-294.

36“Cancellation in defense tenders”, 15 May 2004, Milliyet, http://www.milliyet.com.tr/2004/05/15/

ekonomi/eko02.html

37General Electons 2011: Declaraton of Electon”, AK Party Department of Introducton and Media,

February 2015, p. 84